Catharine Freebody was born around 1784 in Connecticut’s Turkey Hill District, present-day East Granby. Her father, London Freebody, was a veteran of the American Revolution and died before his daughter’s birth. Archival records relating to Catharine's mother have not been located.

Appearing to be orphaned at a young age, Catharine was baptized in the Congregational Church in Turkey Hills and “dedicated by Capt Matthew Griswold & Abiah his Wife who had taken the Child to educate.” Both the 1790 census and 1810 census show a free person of color living in the household of Matthew Griswold in Windsor, though the identity of this person remains unclear. Nonetheless, this early effort by the Griswold family to baptize and “educate” Catharine introduced her to a life of acquaintanceship with Connecticut’s well-known families.

In the 1820 and 1830s, Catharine engaged in a number of legal transactions with several members of the Clark family of Granby as well as a John G. Munn, of Windsor, against whom she won a court judgment. During this time, she sold and leased land in Turkey Hills along the Windsor border.

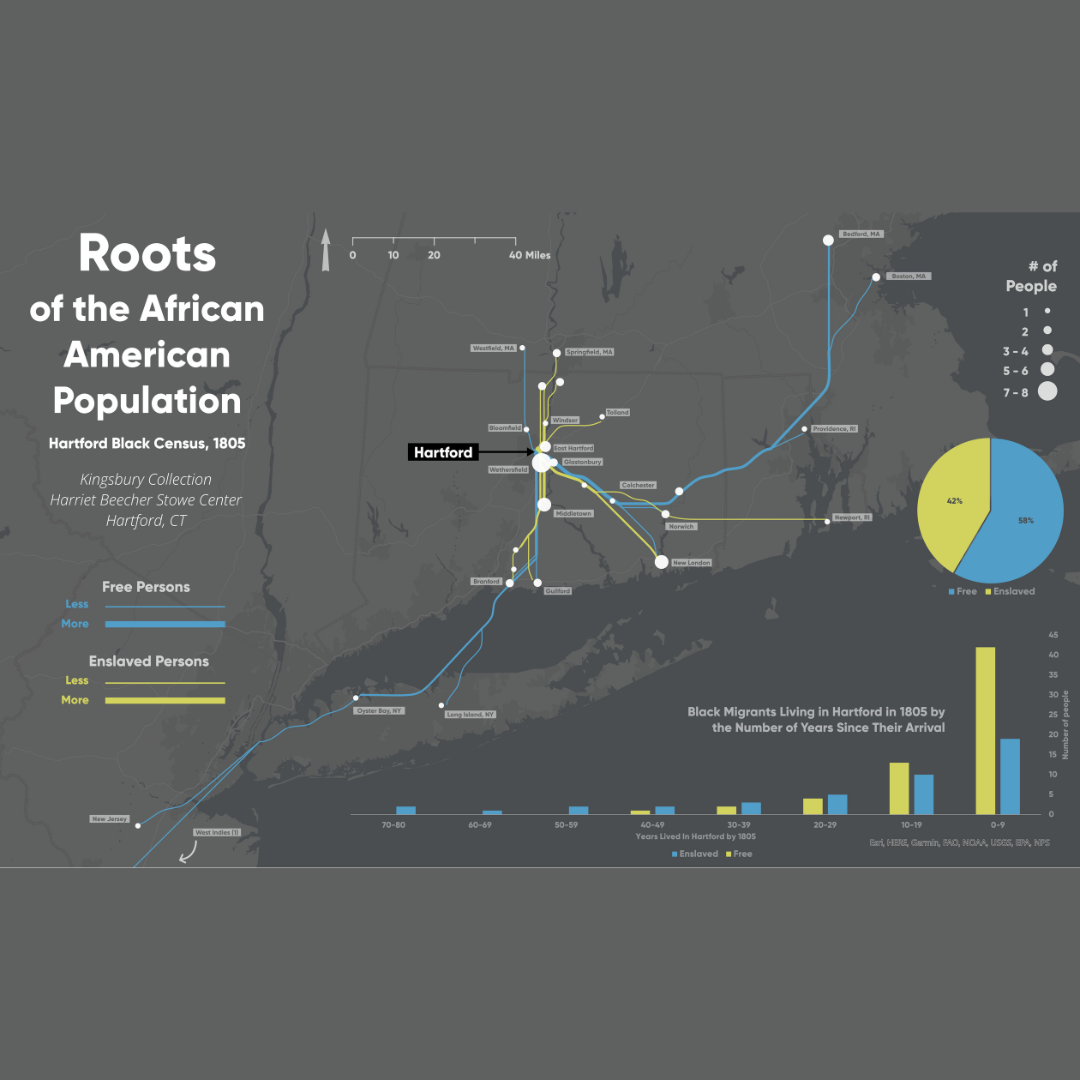

Court records show Catharine living in Hartford by 1821. At this time, the city's African American population was very small and a significant portion of the community lived in white households.

According to the 1830 census, there were 341 African Americans living in Hartford, 206 of which - over 60% - lived in white households. Since Catharine does not appear as a head of household in any census record, she likely lived in one or more of these white households.

After at least a decade of living in Hartford, Catharine united with the First Congregational Church in 1832 at the age of 48.

Catharine likely lived just 500 feet away from her church, where she came to be connected to three of Hartford’s most notable citizens who lived in the same Prospect Street neighborhood: Thomas Scott Williams, former mayor of Hartford, former State Representative, former Congressman, and Chief Justice of Connecticut Supreme Court, then known as the Connecticut Supreme Court of Errors; Williams’ nephew, Judge Francis Parsons; and business magnate, William H. Imlay.

In a triangular relationship the exact details of which remain hazy, Parsons served as Catharine’s straw buyer for a parcel of land sitting down the street of his property. The former chief justice and his wife were two of the three witnesses to Catharine’s will. The land was never conveyed in her lifetime, but instead, was mortgaged to William Imlay, with interest accruing in Catharine’s Society for Savings account. When she died in 1845, Parsons became the executor of her estate and he eventually transferred her property to the First Hartford Colored Congregational Society for a sum of $10, an infinitesimal sum compared to the purchased price of $759 in 1842. By the time the land was sold in 1857, the society netted $1500. This web of relationships suggests Freebody worked for Williams in some capacity and that he, Imlay, and Parsons helped to secure land access for her with her own funds. While Catharine shared an interest in missionary causes with Williams, the lion’s share of her funds supported the religious and educational cause of the Black community in Hartford.

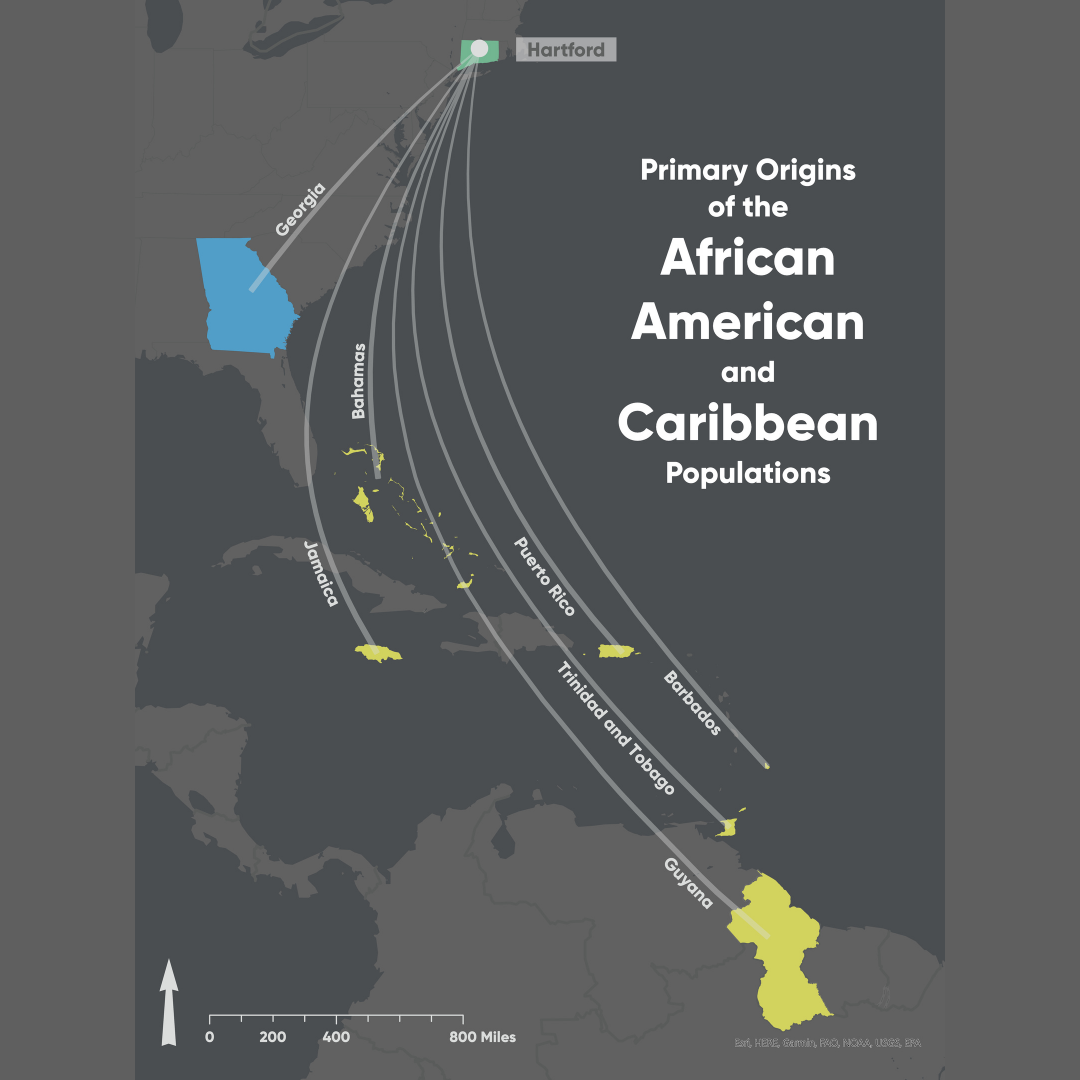

Catharine died on April 5, 1845. In her will, she donated $1,600 to various religious and humanitarian organizations including the American Board of Foreign Missions, American Tract Society, Connecticut Bible Society, Connecticut Missionary Society, Society in Hartford for the Education of Colored Children, and the African Society in Hartford for the Support of Ministry. Word of her philanthropy was published in newspapers in at least 6 cities throughout the United States. This map shows how far her posthumous story traveled.

Catharine's burial location is unknown.

Catharine Freebody

Philanthropist and benefactor with a deep commitment to the cause of Hartford's first African American church.

By the time she died in 1845, Catharine [Catherine] Freebody’s social and economic networks stretched between Granby, Simsbury, Windsor, and Hartford. News of her death and philanthropy was publicized in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New York, Maryland and Ohio. In 61 years she had amassed enough money to become a major benefactor of Hartford’s first African American Church and school; and a supporter of national, international, and local evangelical causes. She left $100 each to the Connecticut Bible Society, the Connecticut Missionary Society, the American Tract Society and to the Education of African American Children. To the American Board of Foreign Missions she donated $200. She left the majority of her estate, $1000, to support the ministry of Hartford’s nascent Black church. Despite an active life devoted to the Congregational Church and deep connections to Hartford’s wealthy and elite, Catharine’s life appears in archival slivers, in land and court records. Given her due as a “worthy colored woman” having “a consistent Christian character,” her friend and kinship networks remain obscure. Below we stitch together the life of Catharine Freebody, an African American woman whose life and contributions made a significant impact on Hartford’s Black community. Using her last will and testament, we mine this moment of agency when, conscious of her legacy, she declared her support for particular Christian causes and earmarked her life savings to future generations of Hartford’s Black community.

Hartford Bound Digital Museum

News & Media

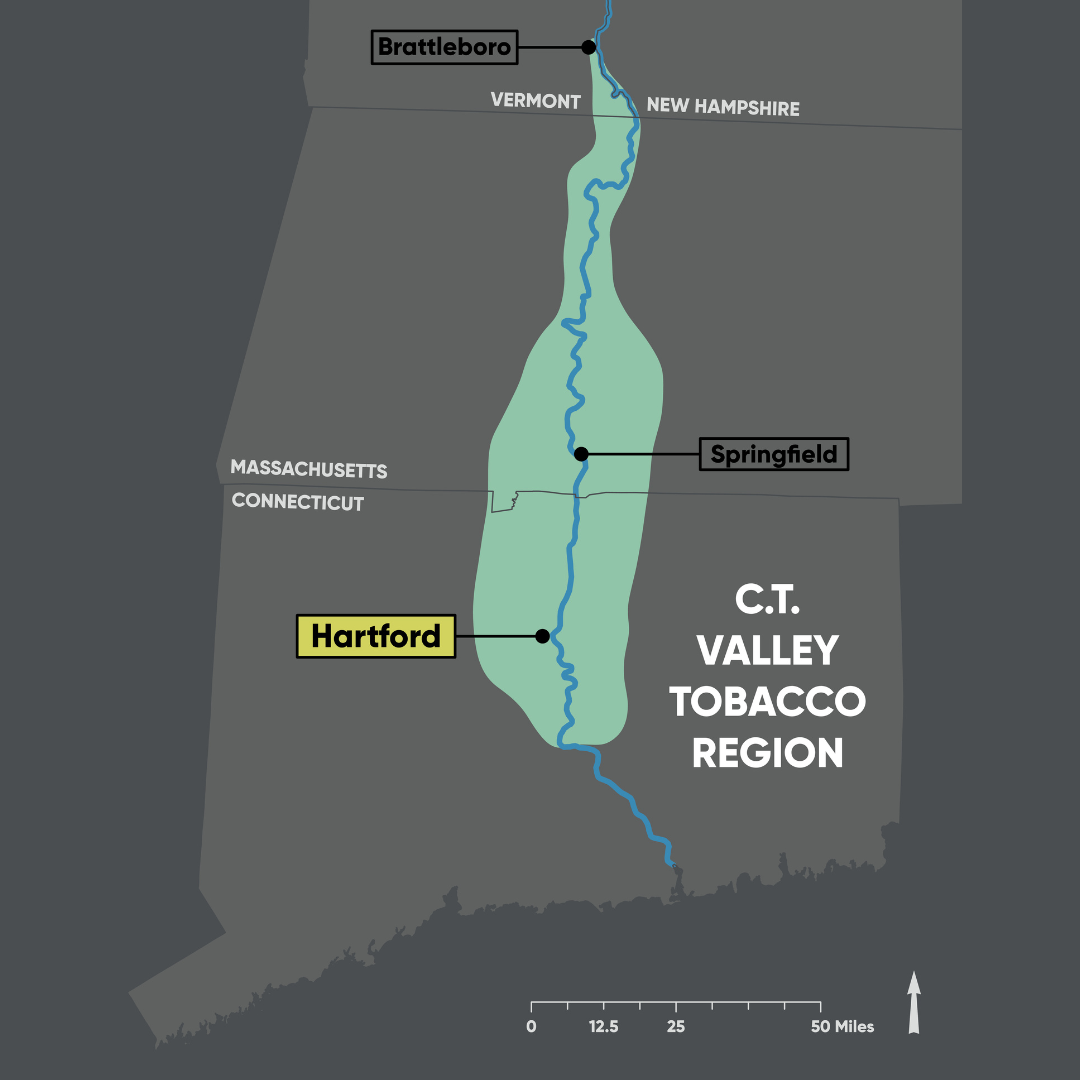

Hispanic Heritage Month: CT Tobacco Industry Impact on Diversity

Between the late 1940s and 1970s, Connecticut saw an influx of migrant workers from Puerto Rico.

&n...

0 Comments